Walking around Berlin today, you could witness his creative mind and influence at the U-Bahn stations, churches, libraries and museums – public venues, which turn the city into an extended living room. Floor-to-ceiling windows, reduced forms and fluid transitions between the inside and the outside characterize Düttmann’s designs. He created architecture that breathes – it may lack decorative elements but still feels adorned. With his notable UdK (University of Arts) building, the St. Agnes church and the Hansa library, Düttmann translated the dynamics of the city into openly flowing spatial sequences.

These buildings are among 28 different sites and locations taking center stage at Werner Düttmann. Building. Berlin exhibition opening on April 17th at the Brücke Museum. The “life size” exhibition tells the story of the buildings and its creator through city walks, video portraits of their residents, films, projections, and Düttmann’s own art collection.

Images: Haus Dr. Menne, Gartenansicht

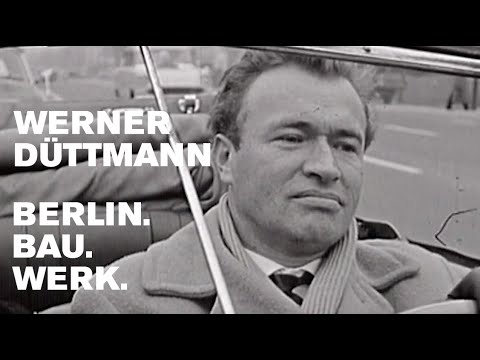

Images: Werner Düttmann, Academy of Arts, Katharina Merz, Hans Düttmann

Images: Werner Düttmann, Skizze des Innenhofes der Akademie der Künste

As an architect, head of the Senate Building Department (1960–66), professor at the Technische Universität of Berlin (1966–70), and president of the Akademie der Künste (1971–83), Düttmann was one of the central figures in the life and culture of West Berlin during his lifetime. In his various functions, he left his mark on the public face and structure of this city — from Reinickendorf to Dahlem, from Neukölln to Spandau. To this day, Werner Düttmann is one of the most important representatives of the post-war Modernism and Brutalism movements.

Emerging in the late 1940s, Brutalism (referring to Le Corbusier and his preference for béton brut, French for “exposed, reinforced concrete”) gave form to the functionalist aspirations of early Modernism while being symptomatic of the moral seriousness that infused a post-war Europe. More than an aesthetic position, it was a movement where architectural ambitions were intimately bound to ideas of social emancipation: this new style of Modernism argued that a democratic society could be created through rationally designed buildings.

In this context of functionality, low cost and innovative aesthetics made concrete widely employed in new structures because of its economic and technical qualities and its incredible plasticity and ability to give shape to the most diverse forms.

Numerous buildings, some of which were erected during this period, are now the focus of controversial discussions: while they are not necessarily aesthetically beautiful for most people due to their, shall we say, brutal appearance, they exert a special fascination for experts and remain the monuments to their time. Unfortunately, most of these projects are crumbling and in need of restoration, while some are subject to demolition. We recently signed a petition to save the Mouse Bunker, undoubtedly the most monumental Brutalist structure in Berlin.

To bring further attention to and awareness of the movement and to celebrate the glorious works of one of its most phenomenal architects, we list our favorite Düttmann’s landmarks around the city. We hope you, too, take a stroll and enjoy the buildings (you might’ve seen many times) with new eyes.

UdK (Universität der Künste), 1958–1960

The Academy (now the University) was a German example of the early period of Brutalism in the spirit of the Hunstanton School. It consists of a three-part ensemble: a bright, cubic exhibition building with a foyer, garden courtyard, and workshops, which interacts with the nature of the surrounding Tiergarten with its open floor-to-ceiling windows, floors lined with slate, the interior wood paneling of Brazilian pine and washed concrete slabs with white Carrara river pebbles on the façade. Behind it, is a multi-purpose red brick building with sloping, low-pitched, patinated copper roofs that contains a studio stage and some other elements. The third structure is a five-story administrative building with additional studios, offices, and conference rooms. Rather than exploring extravagant, sculptural shapes, the focus lies on stripped down aesthetics that unapologetically expose the building’s structure and materials.

By loading the video, you agree to YouTube's privacy policy.

Learn more

St. Agnes (today: König Galerie), 1965–1967

An iconic Brutalist church completed in 1967 by Werner Düttmann, St. Agnes underwent renovations by architect Arno Brandlhuber before becoming the permanent residence of König Galerie. The concrete monolith has no windows, but its exhibition halls are light filled thanks to slits in its facade and skylights. A concrete nave, corner to corner stands the bell tower at the church building, on top of it a concrete cube that seems to float. Two vertical window slits in the walls and window bands in the roof light up the concrete church room with daylight.

Berlin Interbau/Hansaviertel (1957-1960)

In response to Stalinallee, Interbau 1957 presented a model for the city of tomorrow. Under the leadership of Otto Bartning, the new, upper-class Hansaviertel district became a prestige project to demonstrate the superiority of the West over the East. Based on an urban development competition, 53 internationally renowned architects, including Oscar Niemeyer, Arne Jacobsen, Alvar Aalto and the German Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, were selected to create a mixture of high-rise and low-rise buildings in the heart of a park landscape. Werner Düttmann designed the Hansa library, with an architectural concept of dissolution of boundaries between interior and exterior and with different room and mood offerings. The Hansaviertel district is now considered an example of large-scale modernist refurbishment for urban developers.

Brücke Museum (1966-1967)

The one-story, flat-roofed building stretches out under the old pines and birch trees. Built like a bungalow, it fits in harmoniously with the quiet, exclusive residential area of Dahlem. With its clean and functional architectural forms, the building follows the Bauhaus tradition. It is a typical example of the German architecture of the 1960s with aesthetic principles of classical modernity. The building's strength lies in its quiet intimacy and conscious spatial reduction, which serve the museum's real purpose in an ideal way: a focused presentation of life and work of the Die Brücke artists.

Images: Brücke-Museum, Außenansicht, September 1967

Images: Installationsansicht, Brücke-Museum

Images: Installationsansicht, Brücke-Museum

Images: St. Agnes, Auáenansicht

Images: Akademie der Künste, Eröffnung am 18. Juni 1960

Images: Akademie der Künste, Blick über das Bauensemble

Related Articles: