A few days later, we step into her world — into her atelier in Berlin-Mitte, which is not just an office or a store, but a living, breathing creative space. A black universe where fabrics, ideas, and identities melt together. Where trends don’t matter, but meaning does. Here, we meet Esther, the artist and designer who has built her own orbit in Berlin. What unfolds is not just a conversation — but a look into a life lived with fearless conviction.

— What was the most memorable moment that made you the designer you are today?

— That’s a deep question. I always say that the reason I became a fashion designer has a lot to do with my childhood. I knew by the age of twelve that I wanted to become a designer. I grew up without a TV, without a mobile phone, without the internet. I had a huge dressing cabinet — it was like a paradise for me. It was so big I could sleep inside it, and it was full of all kinds of stuff. I just loved dressing up, trying on things, going out in new outfits. I wasn’t aware of it back then, but I understood even as a kid that clothing lets you slip into different roles and identities.

It continued with Barbie, of course. But not in a typical way — my friend once said playing Barbie with me was boring because all I wanted to do was dress and undress them. No storyline, no plot.

I experimented with clothes early. I was a huge Madonna fan. When Desperately Seeking Susan came out, I was in elementary school and I turned ten. For my birthday, I went to school dressed like Madonna. I had just gotten my ears pierced — with two earrings in one ear, not one in each. I thought, “Now I’m a punk. Now I’m Madonna. And a rebel.” That day was really important. I think that was when the path was laid.

ㅤ

— How would you describe your younger self in three words?

— Stubborn. Always wanted to be different. Restless.

— Which of those traits stayed with you?

— All three. You can still see it.

— When do you feel most connected to your creativity?

— In silence. Always. I never listen to music — not at home, not while working. I need absolute silence to go deep into my world. Music is important to me as inspiration, but not during the process. Most of my ideas come to me when I’m alone — in the shower, or at random moments. That’s when I feel most connected.

— What did Berlin give you that Paris or Moscow couldn’t — and vice versa?

— I always say I’m a mix of three cities. Berlin is my root. Here I feel safe, at home, uplifted. Berlin gave me rock’n’roll, punk, thinking outside the box — doing things your own way, playing by the rules and then twisting them.

Then I spent time in Moscow, which influenced me deeply. I drew a lot of inspiration from uniforms, from the Russian avant-garde of the 1920s. And Paris, where I studied and worked later at the Côte d’Azur, gave me elegance and refinement. I love elegance. But my work is always a mix — never purely elegant. It’s a play between masculine and feminine. It must always be slightly broken, never clean-cut.

— Your designs are often described as androgynous.

— They were androgynous. But in the last few years, I’ve transitioned from being a sort of androgynous tin soldier to embracing strong femininity — both in myself and in my design. For me, creating collections is like writing a diary. You can look at a collection from ten years ago and instantly feel where I was — physically and emotionally.

When I was a teenager, I didn’t want to be a woman. I dressed like a man. It was a protective shield. That stayed with me for many years. I started doing unisex fashion twenty years ago, when no one else really was. I used to call it “customized fashion.” But I also realized that if I kept saying that, I’d lose potential clients — especially women with curves, with busts. If they heard “unisex” once, they wouldn’t even walk into my store.

Now I say it’s gender-fluid — you can wear it whether you’re a man, woman, or non-binary, and it will look the same. But over time, I started designing the same blazer in two cuts: one for men, one for women. You might not notice it in a photo, but the cut acknowledges different bodies. Men and women are not the same — women have hips, breasts, curves. I don’t differentiate in style, but I do in tailoring.

There are very feminine things in my collections now. And I sometimes feel very feminine, too — just in a way that doesn’t tick traditional boxes.

— When did you realize you weren’t just building a fashion label, but an entire universe?

— I never consciously decided that. It all came from necessity. The only thing I cared about was keeping the label alive. It’s my baby. I never wanted anything else. But I had to find workarounds to make it work — many decisions were made intuitively.

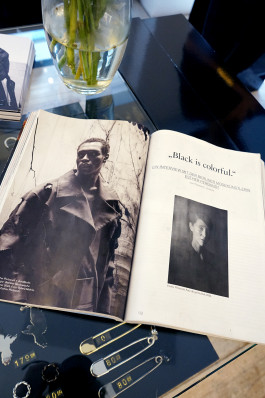

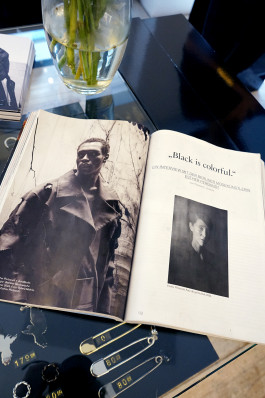

Like when I realized I feel strongest when I wear black. So I banned all colors. That was one of the smartest moves I ever made. Because everything was black, I could establish classics that never go out of stock. I could reuse fabrics over and over. I don’t throw anything away. Every fabric is used until it’s completely gone.

People who use new fabrics each season end up with massive leftover stock. For me, that black-only concept brought a kind of sustainability. Again, I didn’t plan it — it was intuitive. But years later I can look back and say: that was a very clever move.

— Do you always wear black?

— Yes. Though sometimes, when I get invited to fashion parties, I play around — costumes, themes, pinks. But usually? Only black.

— Never tempted by pink?

— (Laughs) But I love seeing others dress colorfully — it’s just not me.

— This space we’re in — it’s like a little magic workshop.

— Downstairs is the shop, and in the back is the office, where everything happens. But here… this is where ideas come to life. I’m not here often, honestly — I’m 98% CEO and only 2% designer most days. But this space? That’s where my heart is.

— What’s it like when you’re actually creating?

— When I’m working with Natalia, my tailor, or an intern — sketching, cutting, building — it feels like I’m six years old again, playing on the playground. It’s pure joy. The process always changes. I might design something on paper, but paper is patient. Reality is different. Sometimes the piece ends up totally transformed, and that’s the beauty of it. You have to be present, hands-on, and ready to say, “Stop. That wasn’t the plan — but wait, it actually looks better now.” Or sometimes: “No, this isn’t working. We need a new solution.”

— How big is your team?

— Very small. It’s me, Ella — my full-time assistant — and Natalia, my tailor. She works 20 hours a week. And we usually have one trainee. So, two and a half people, really. That’s the whole team.

— How do you develop new pieces? What inspires you? And where is it produced?

— It’s not like I go to a museum and then get inspired. It’s intuitive. A teacher in Paris once told me: “Design for yourself, not others.” That changed me. After 18 years of working directly with customers, I know who they are. My collections are always a mix of what I would wear and what I know my clients want. That blend is my DNA.

Most of my production is in Poland. I make small series there. When a size sells out, I sometimes produce it in Berlin. That costs more, but it becomes a one-off. We also do custom production.

— How important is the dialogue with the people who wear your pieces?

— It’s everything. I offer the piece, but it becomes something else on a different body. That feedback loop shapes how I design.

— How did participating in “Making the Cut” affect you?

— At first, I thought it might destroy everything I’d built. But it did the opposite. It brought me international visibility, especially in the U.S. It kept my brand alive during the pandemic. And I stayed true to myself — I didn’t add color, even though the jury pushed for it. That earned me unexpected respect.

— You often work with musicians, dancers, and artists. Where do you draw the line between fashion and performance?

— That has changed. In the past, I did many performative shows, worked with dancers and musicians. Recently, I’ve separated it more. I still create textile art — landscapes for exhibitions using the same materials. I had a solo show in Leipzig and have participated in Berlin’s art fair for five years. My fashion and art still intermingle.

But I’m more focused on the collection itself now. A while back, someone criticized me for letting the show overshadow the clothes. That hit hard — but it wasn’t entirely wrong. Now I focus on the pieces themselves. My latest presentation was small and intimate. No musicians, no theatrics — just the clothes, viewed up close. That felt right.

— Advice for young creatives?

— Listen to yourself. That’s my best advice. Over 21 years, I’ve had so many conversations with people — mostly men — who thought they knew better. They gave advice that made me question myself. But they had no idea how I survive or how I work. I call myself the queen of survival. Only I know which screws to turn.

Take all advice, but don’t take it too seriously. And allow yourself a big dose of naivety. If I’d known back then how hard it would be, I’d never have started. But you learn by doing. Most creatives have no business background. You fall, scrape your knees, and get back up. Berlin is a great place for that. You’re allowed to make mistakes here. You need to make mistakes to grow.

Marina Abramović said it beautifully — creativity means trying, failing, and daring to do more. That’s how you move forward.

— Berlin Fashion Week — what stood out to you this season?

— So many new names. The calendar was packed. And the Fashion Council brought in international press. Berlin is finally being recognized for its own voice — not as a copy of Paris or New York.

— What are your hopes for Berlin Fashion Week going forward?

— I hope it continues to grow — and I believe it will. Every journalist or guest I’ve spoken to has said they want to come back. The calendar is well-structured now, there’s order and good media coverage. I can’t complain.

Beyond Fashion Week, Berlin needs to preserve its retail landscape. Every city is starting to look the same. Berlin has always been a magnet because of its small, unique shops. But rising rents are threatening that.

— Why don’t you follow seasonal collections?

— I design what I call an “eternal collection.” Pieces return. It’s sustainable, slower, more real. When something sells out, we make it again — or upgrade it. No one needs a new wardrobe every six months.

— How has digital production changed your work?

— Hugely. We use Clo3D now — a 3D tool that lets us visualize everything before we cut fabric. We’ve made wedding dresses this way without fittings. It saves waste and time.

— What are your thoughts on gender and style?

— I sell around 80% to women and 20% to men — but more men are coming. Some buy full looks — jackets, trousers, even skirts. It’s evolving. One classic is my J-Bow Pants, first designed in 2009. They still hang in my store today.

— Any dreams or collaborations you’re still hoping to realize?

— There are so many things I’d love to do — not because I lack the courage, but because I lack the resources. I’d love to expand into sportswear, swimwear, eyewear, bags, even shoes. But I can’t do it alone. It would require a license or a collaboration.

A particularly beautiful moment for me was during Making the Cut, episode two — the haute couture challenge. I studied in Paris and spent so much time at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, where fashion is truly celebrated. That moment brought me full circle.

They always touched me when I was there. I used to visit alone because I knew, at some point, the tears would start rolling down my face. I was just so moved. I’m fascinated by clothing and fashion — something about it deeply stirs me. The tears would come because I’d think, “Oh God, maybe one day I’ll be exhibited here.”

Then on Making the Cut, the second episode was about haute couture. The fashion show was held in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs — not in the actual exhibition rooms, but in the same building, in a huge hall. Still, it was the same house.

— That must have been emotional.

— It really was. Standing in that enormous, historic space in Paris, being filmed, being called forward... There was a monitor where I saw my two looks — and I had to bite my lips. I just thought, “Oh no.” When it was over, I ran to a corner of the building and cried. I had created haute couture pieces. I had never done that before.

I bought 20 meters of tulle and sequined fabric — materials I’d never worked with. I made a dress like I’d never made before. And it’s still there. It was one of the most powerful moments of my life.

— Would you like to do more couture?

— Absolutely. But there’s a hurdle — I often don’t allow myself to go there. I'm afraid. I mean, I can’t just create a dress for 10,000 euros — I don’t have the customer base for that yet. But if I could, I would. If anyone reading this wants to support that dream — I'm here.

— What gives you the courage to stay so bold and radical in your work?

— That’s a beautiful question. I’m not even sure I know the answer. You must see something in me — otherwise you wouldn’t ask. But I don’t always feel that way.

I think this brings us full circle, back to your very first question: How would you describe yourself? Maybe that little Esther. It’s this boldness. When I want something, I go for it.

There’s something inside me, like an engine that just keeps going. A fire. Even if I don’t always know where it’s headed.

As we wrap up our conversation, I glance at the little girl inside her — the one with a dream, who was bold enough to follow it through and turn it into something real. It's beautiful to witness someone who dared.

To Esther, we wish nothing less than ever-greater heights, new frontiers, and bold new ideas. After all, it is the fearless who conquer the seas.

Related Articles:

A few days later, we step into her world — into her atelier in Berlin-Mitte, which is not just an office or a store, but a living, breathing creative space. A black universe where fabrics, ideas, and identities melt together. Where trends don’t matter, but meaning does. Here, we meet Esther, the artist and designer who has built her own orbit in Berlin. What unfolds is not just a conversation — but a look into a life lived with fearless conviction.

— What was the most memorable moment that made you the designer you are today?

— That’s a deep question. I always say that the reason I became a fashion designer has a lot to do with my childhood. I knew by the age of twelve that I wanted to become a designer. I grew up without a TV, without a mobile phone, without the internet. I had a huge dressing cabinet — it was like a paradise for me. It was so big I could sleep inside it, and it was full of all kinds of stuff. I just loved dressing up, trying on things, going out in new outfits. I wasn’t aware of it back then, but I understood even as a kid that clothing lets you slip into different roles and identities.

It continued with Barbie, of course. But not in a typical way — my friend once said playing Barbie with me was boring because all I wanted to do was dress and undress them. No storyline, no plot.

I experimented with clothes early. I was a huge Madonna fan. When Desperately Seeking Susan came out, I was in elementary school and I turned ten. For my birthday, I went to school dressed like Madonna. I had just gotten my ears pierced — with two earrings in one ear, not one in each. I thought, “Now I’m a punk. Now I’m Madonna. And a rebel.” That day was really important. I think that was when the path was laid.

ㅤ

— How would you describe your younger self in three words?

— Stubborn. Always wanted to be different. Restless.

— Which of those traits stayed with you?

— All three. You can still see it.

— When do you feel most connected to your creativity?

— In silence. Always. I never listen to music — not at home, not while working. I need absolute silence to go deep into my world. Music is important to me as inspiration, but not during the process. Most of my ideas come to me when I’m alone — in the shower, or at random moments. That’s when I feel most connected.

— What did Berlin give you that Paris or Moscow couldn’t — and vice versa?

— I always say I’m a mix of three cities. Berlin is my root. Here I feel safe, at home, uplifted. Berlin gave me rock’n’roll, punk, thinking outside the box — doing things your own way, playing by the rules and then twisting them.

Then I spent time in Moscow, which influenced me deeply. I drew a lot of inspiration from uniforms, from the Russian avant-garde of the 1920s. And Paris, where I studied and worked later at the Côte d’Azur, gave me elegance and refinement. I love elegance. But my work is always a mix — never purely elegant. It’s a play between masculine and feminine. It must always be slightly broken, never clean-cut.

— Your designs are often described as androgynous.

— They were androgynous. But in the last few years, I’ve transitioned from being a sort of androgynous tin soldier to embracing strong femininity — both in myself and in my design. For me, creating collections is like writing a diary. You can look at a collection from ten years ago and instantly feel where I was — physically and emotionally.

When I was a teenager, I didn’t want to be a woman. I dressed like a man. It was a protective shield. That stayed with me for many years. I started doing unisex fashion twenty years ago, when no one else really was. I used to call it “customized fashion.” But I also realized that if I kept saying that, I’d lose potential clients — especially women with curves, with busts. If they heard “unisex” once, they wouldn’t even walk into my store.

Now I say it’s gender-fluid — you can wear it whether you’re a man, woman, or non-binary, and it will look the same. But over time, I started designing the same blazer in two cuts: one for men, one for women. You might not notice it in a photo, but the cut acknowledges different bodies. Men and women are not the same — women have hips, breasts, curves. I don’t differentiate in style, but I do in tailoring.

There are very feminine things in my collections now. And I sometimes feel very feminine, too — just in a way that doesn’t tick traditional boxes.

— When did you realize you weren’t just building a fashion label, but an entire universe?

— I never consciously decided that. It all came from necessity. The only thing I cared about was keeping the label alive. It’s my baby. I never wanted anything else. But I had to find workarounds to make it work — many decisions were made intuitively.

Like when I realized I feel strongest when I wear black. So I banned all colors. That was one of the smartest moves I ever made. Because everything was black, I could establish classics that never go out of stock. I could reuse fabrics over and over. I don’t throw anything away. Every fabric is used until it’s completely gone.

People who use new fabrics each season end up with massive leftover stock. For me, that black-only concept brought a kind of sustainability. Again, I didn’t plan it — it was intuitive. But years later I can look back and say: that was a very clever move.

— Do you always wear black?

— Yes. Though sometimes, when I get invited to fashion parties, I play around — costumes, themes, pinks. But usually? Only black.

— Never tempted by pink?

— (Laughs) But I love seeing others dress colorfully — it’s just not me.

— This space we’re in — it’s like a little magic workshop.

— Downstairs is the shop, and in the back is the office, where everything happens. But here… this is where ideas come to life. I’m not here often, honestly — I’m 98% CEO and only 2% designer most days. But this space? That’s where my heart is.

— What’s it like when you’re actually creating?

— When I’m working with Natalia, my tailor, or an intern — sketching, cutting, building — it feels like I’m six years old again, playing on the playground. It’s pure joy. The process always changes. I might design something on paper, but paper is patient. Reality is different. Sometimes the piece ends up totally transformed, and that’s the beauty of it. You have to be present, hands-on, and ready to say, “Stop. That wasn’t the plan — but wait, it actually looks better now.” Or sometimes: “No, this isn’t working. We need a new solution.”

— How big is your team?

— Very small. It’s me, Ella — my full-time assistant — and Natalia, my tailor. She works 20 hours a week. And we usually have one trainee. So, two and a half people, really. That’s the whole team.

— How do you develop new pieces? What inspires you? And where is it produced?

— It’s not like I go to a museum and then get inspired. It’s intuitive. A teacher in Paris once told me: “Design for yourself, not others.” That changed me. After 18 years of working directly with customers, I know who they are. My collections are always a mix of what I would wear and what I know my clients want. That blend is my DNA.

Most of my production is in Poland. I make small series there. When a size sells out, I sometimes produce it in Berlin. That costs more, but it becomes a one-off. We also do custom production.

— How important is the dialogue with the people who wear your pieces?

— It’s everything. I offer the piece, but it becomes something else on a different body. That feedback loop shapes how I design.

— How did participating in “Making the Cut” affect you?

— At first, I thought it might destroy everything I’d built. But it did the opposite. It brought me international visibility, especially in the U.S. It kept my brand alive during the pandemic. And I stayed true to myself — I didn’t add color, even though the jury pushed for it. That earned me unexpected respect.

— You often work with musicians, dancers, and artists. Where do you draw the line between fashion and performance?

— That has changed. In the past, I did many performative shows, worked with dancers and musicians. Recently, I’ve separated it more. I still create textile art — landscapes for exhibitions using the same materials. I had a solo show in Leipzig and have participated in Berlin’s art fair for five years. My fashion and art still intermingle.

But I’m more focused on the collection itself now. A while back, someone criticized me for letting the show overshadow the clothes. That hit hard — but it wasn’t entirely wrong. Now I focus on the pieces themselves. My latest presentation was small and intimate. No musicians, no theatrics — just the clothes, viewed up close. That felt right.

— Advice for young creatives?

— Listen to yourself. That’s my best advice. Over 21 years, I’ve had so many conversations with people — mostly men — who thought they knew better. They gave advice that made me question myself. But they had no idea how I survive or how I work. I call myself the queen of survival. Only I know which screws to turn.

Take all advice, but don’t take it too seriously. And allow yourself a big dose of naivety. If I’d known back then how hard it would be, I’d never have started. But you learn by doing. Most creatives have no business background. You fall, scrape your knees, and get back up. Berlin is a great place for that. You’re allowed to make mistakes here. You need to make mistakes to grow.

Marina Abramović said it beautifully — creativity means trying, failing, and daring to do more. That’s how you move forward.

— Berlin Fashion Week — what stood out to you this season?

— So many new names. The calendar was packed. And the Fashion Council brought in international press. Berlin is finally being recognized for its own voice — not as a copy of Paris or New York.

— What are your hopes for Berlin Fashion Week going forward?

— I hope it continues to grow — and I believe it will. Every journalist or guest I’ve spoken to has said they want to come back. The calendar is well-structured now, there’s order and good media coverage. I can’t complain.

Beyond Fashion Week, Berlin needs to preserve its retail landscape. Every city is starting to look the same. Berlin has always been a magnet because of its small, unique shops. But rising rents are threatening that.

— Why don’t you follow seasonal collections?

— I design what I call an “eternal collection.” Pieces return. It’s sustainable, slower, more real. When something sells out, we make it again — or upgrade it. No one needs a new wardrobe every six months.

— How has digital production changed your work?

— Hugely. We use Clo3D now — a 3D tool that lets us visualize everything before we cut fabric. We’ve made wedding dresses this way without fittings. It saves waste and time.

— What are your thoughts on gender and style?

— I sell around 80% to women and 20% to men — but more men are coming. Some buy full looks — jackets, trousers, even skirts. It’s evolving. One classic is my J-Bow Pants, first designed in 2009. They still hang in my store today.

— Any dreams or collaborations you’re still hoping to realize?

— There are so many things I’d love to do — not because I lack the courage, but because I lack the resources. I’d love to expand into sportswear, swimwear, eyewear, bags, even shoes. But I can’t do it alone. It would require a license or a collaboration.

A particularly beautiful moment for me was during Making the Cut, episode two — the haute couture challenge. I studied in Paris and spent so much time at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, where fashion is truly celebrated. That moment brought me full circle.

They always touched me when I was there. I used to visit alone because I knew, at some point, the tears would start rolling down my face. I was just so moved. I’m fascinated by clothing and fashion — something about it deeply stirs me. The tears would come because I’d think, “Oh God, maybe one day I’ll be exhibited here.”

Then on Making the Cut, the second episode was about haute couture. The fashion show was held in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs — not in the actual exhibition rooms, but in the same building, in a huge hall. Still, it was the same house.

— That must have been emotional.

— It really was. Standing in that enormous, historic space in Paris, being filmed, being called forward... There was a monitor where I saw my two looks — and I had to bite my lips. I just thought, “Oh no.” When it was over, I ran to a corner of the building and cried. I had created haute couture pieces. I had never done that before.

I bought 20 meters of tulle and sequined fabric — materials I’d never worked with. I made a dress like I’d never made before. And it’s still there. It was one of the most powerful moments of my life.

— Would you like to do more couture?

— Absolutely. But there’s a hurdle — I often don’t allow myself to go there. I'm afraid. I mean, I can’t just create a dress for 10,000 euros — I don’t have the customer base for that yet. But if I could, I would. If anyone reading this wants to support that dream — I'm here.

— What gives you the courage to stay so bold and radical in your work?

— That’s a beautiful question. I’m not even sure I know the answer. You must see something in me — otherwise you wouldn’t ask. But I don’t always feel that way.

I think this brings us full circle, back to your very first question: How would you describe yourself? Maybe that little Esther. It’s this boldness. When I want something, I go for it.

There’s something inside me, like an engine that just keeps going. A fire. Even if I don’t always know where it’s headed.

As we wrap up our conversation, I glance at the little girl inside her — the one with a dream, who was bold enough to follow it through and turn it into something real. It's beautiful to witness someone who dared.

To Esther, we wish nothing less than ever-greater heights, new frontiers, and bold new ideas. After all, it is the fearless who conquer the seas.

Related Articles:

You need to load content from reCAPTCHA to submit the form. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou need to load content from Turnstile to submit the form. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou are currently viewing a placeholder content from Facebook. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou are currently viewing a placeholder content from Instagram. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou need to load content from hCaptcha to submit the form. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou need to load content from reCAPTCHA to submit the form. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou are currently viewing a placeholder content from Turnstile. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information